vapes

Disposable Vapes in the UK – Thriving Underground Market for Sustainable Alternatives

When the United Kingdom officially banned the sale of single-use nicotine vapes on June 1, policymakers framed it as a decisive move to curb youth vaping and tackle environmental waste. But just weeks later, an undercover investigation revealed a different reality: demand for disposables remains high, enforcement is inconsistent, and the market is adapting in ways regulators may not have anticipated.

The probe, conducted by the online nicotine retailer Haypp, sent mystery shoppers to 48 stores across nine UK cities between June 2 and June 6. From independent vape shops in Glasgow to convenience chains in Birmingham, nearly one in four retailers were willing to sell banned products. Some transactions were disguised – cash only, no receipts, bulk packages instead of individual units – making detection even harder.

“We’re not surprised about the results,” said Markus Lindbald, Haypp’s head of Legal & External Affairs. “If the government doesn’t enforce the law, businesses will simply take the opportunity to profit.”

The findings confirmed what tobacco harm reduction advocates had warned months earlier: without clear enforcement strategies, the ban would simply push sales underground. And that’s only part of the story. The investigation didn’t account for informal sales through social media, markets, or personal networks – spaces where regulation is even harder to reach.

A Policy Caught Between Health and Habit

The UK government justified the ban on two grounds: protecting minors and reducing environmental damage. Disposable vapes are often brightly packaged, flavoured in ways that appeal to younger consumers, and thrown away after just a few days of use, contributing to electronic waste.

Yet, many public health advocates opposed a blanket prohibition. They argued disposables are often the easiest and cheapest gateway for smokers – especially those in disadvantaged communities – to switch from cigarettes to vaping. Removing them overnight, they warned, risked pushing some users back to tobacco or into the hands of unregulated sellers.

Research from Action on Smoking and Health supports those fears: nearly half of underage vapers surveyed said they would seek illicit disposables after the ban.

The Rise of “Legal” Disposables in Disguise

Ironically, many of the reusable devices now hitting UK shelves look and feel almost identical to the banned disposables – same shape, same bright colours, same sweet flavours. According to the consultancy Broughton, this shift was predictable: manufacturers have simply pivoted to pod-based systems while retaining the appeal of their most popular disposable lines.

Some of these devices are technically reusable, with USB charging ports and refillable pods, but early sales data shows a troubling pattern: far more devices are being sold than refill cartridges. This suggests many consumers are discarding “reusables” after a single use – essentially turning them into legal disposables.

Environmental Stakes and the Push for Accountability

The environmental case against single-use vapes is stark. Lithium batteries, plastic housings, and residual nicotine can leach into soil and water if discarded improperly. In just three years, the rare earth materials wasted from disposed vapes in the UK could have powered over 16,000 electric cars, according to Material Focus.

Globally, advocacy groups like the Coalition of Asia Pacific Tobacco Harm Reduction Advocates are calling for stronger producer responsibility. In New Zealand, the VapeCycle program collects and processes used devices, preventing them from ending up in landfills. Similar models, they say, could be replicated elsewhere.

The UK is now moving toward a “polluter pays” principle, requiring vape manufacturers and sellers – online and offline – to fund the collection and recycling of their products. Even overseas vendors selling to UK consumers will be obligated to register, track sales, and contribute financially to waste management.

Innovation and the Search for a Middle Ground

The industry has not stood still. Brands are developing high-capacity rechargeable disposables that last far longer than traditional single-use devices, reducing both waste and cost per puff. Examples include:

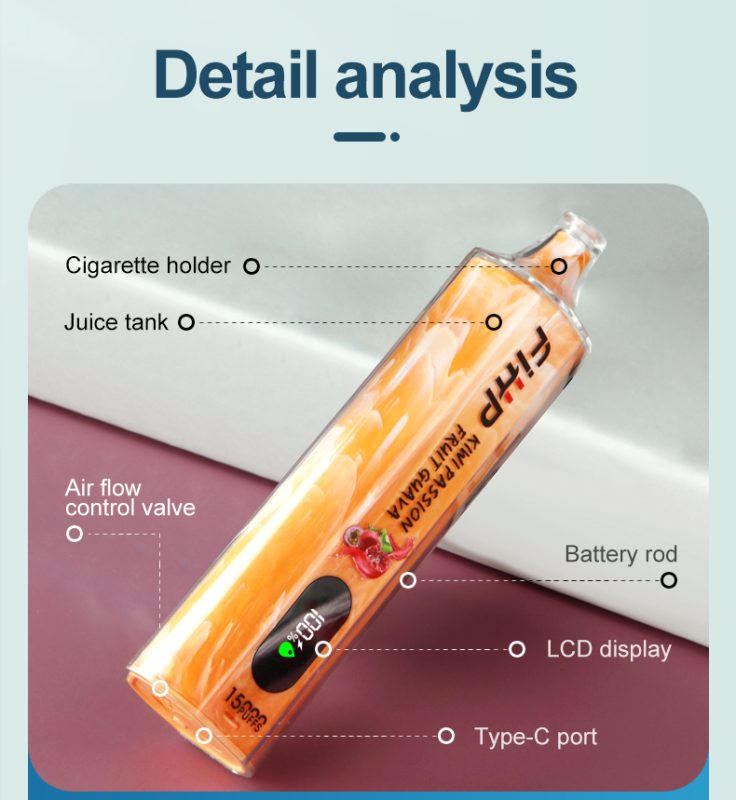

MEMERS V40000 – A 15 ml, 2600 mAh disposable capable of delivering up to 40,000 puffs, complete with a screen showing battery and e-liquid levels.

Vaporesso Eco Nano – A compact pod vape with a 6 ml refillable pod and rechargeable 1000 mAh battery, offering thousands of puffs per coil.

iJoy SD22000 – A rechargeable disposable with 30 ml of e-liquid in dual tanks, designed for up to 22,000 puffs.

Smok Infinix – A slim, refillable pod system with pass-through charging for convenience.

These devices blend the convenience of disposables with the sustainability of reusables, giving consumers options that are both practical and environmentally conscious.

For policymakers, the challenge is finding a path that protects young people, safeguards the environment, and preserves vaping as a harm-reduction tool for adult smokers. Heavy-handed bans risk fuelling black markets; too-light regulation risks perpetuating the waste problem.

The solution, many argue, lies in better enforcement, smarter product design, and meaningful recycling infrastructure. If manufacturers can produce vapes that are durable, affordable, and easy to recycle – and if governments can ensure these are the products people actually buy – then the UK might finally break the cycle of “use and discard.”